The Town Trail

A Bridgwater Walkabout prepared for the Bridgwater and District Civic Society

by J. F. Lawrence, M.A., M.Litt.

After the year 1200 Bridgwater grew into an important town. Its importance derived from commerce. Bridgwater was the natural outlet for a cloth-producing region; the cloth which was collected here in the hands of the merchants became known as Bridgwater Cloth. It was the chief export that went °verseas from the port, mainly to France. The West Country cloth industry was eventually killed by the Industrial Revolution in Yorkshire in the 18th century.

Before 1800 one or two enterprising persons began to make bricks and tiles from the raw material, clay, which lay around them in such abundance. By 1841 hundreds of workers were employed in the Bridgwater brick industry and a floating dock was constructed for the more efficient handling of shipping. In the 1840’s the railways began to offer a rival method of transport for trade and the gradual decline of the docks began to make itself noticeable after 1879. Not until 1945 did the brick and the industry decline, and then the decline was sudden. Today the industry is just a memory.

Bridgwater has Conservation Areas where most of its best buildings are to be found. Only two of these buildings, apart from St. Mary’s Church, can by any stretch of the imagination be called medieval. Both are c 1500. They are No. 47 St. Mary Street and No. 5 Blake Street (the Town Museum).

Unfortunately for our purpose (i.e. sightseeing) the streets are frequently full of traffic and the pavements crowded. The best time for doing a Town Walk is on a Sunday. It is difficult to visualise a building as a whole when you cannot see the ground floor. Even when the streets are deserted this problem has not really been solved because in a busy commercial centre most buildings have lost the original ground floor in order to make way for shops. Only the trained eye of a professional architect can visualise the original design. The rest of us must make shift as well as we can with what is left, above the level of the shop fronts.

Whatever we do, we must certainly watch the roof line. The older streets such as High Street, Fore Street and Friarn Street have an extremely interesting roof line. There are many mansard roofs which tell us that the building below is probably of late 18th century date. Where gables are visible you will notice that some are pierced by a small circular window. Sometimes a roof parapet has been added to conceal the attic windows of the mansard. “Spotting” them can be a fascinating game. Many houses of 18th and 19th century date have roof parapets A varying heights, design and proportions. (Contrast all this with the monotonous regularity of the roof line in a modern housing estate).

Do not forget to stand, at the appropriate point (i.e. No. 28 below) on the south side of the bridge in order to examine the façade of No. 2 Fore Street. This displays a most extraordinary collection of “Edwardian baroque” motifs. Above it is a hipped roof crowned by a massive brick chimney elaborately moulded, from the four corners of which writhing serpents are silhouetted against the sky. But the oddest building in the whole of Bridgwater is a house in Queen Street No. 17. approached from the bottom of Castle Street. This is entirely constructed from concrete. It was conceived in the late 19th century by a local business man who intended to create an interest in concrete as a new building material. The design of the house and the design of details such as mouldings, friezes and roof parapet are incredibly bad. It is small wonder that the experiment failed to make the new building material popular. Two streets now included in Conservation Areas but not touched on in this Walkabout are: Church Street (off Eastover) and Northfield (to the west of As town).

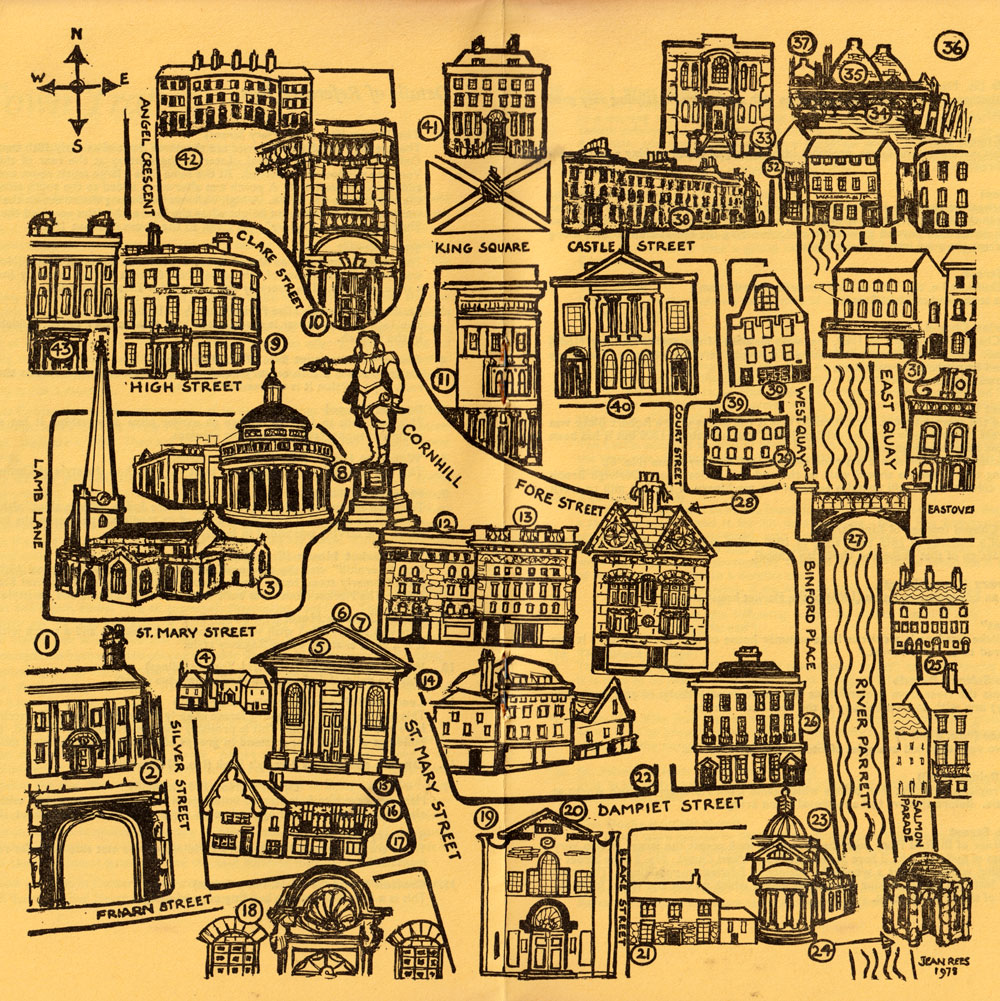

Details of Reference Nos. to the 1978 Town Trail

1. The Priory (No. 69 St. Mary Street) The five bays which face the road are the north front of an early 18th century town house. Only the doorway is original. Later in the century at the rear of this building a fine Venetian window was inserted. At the same time a large music room and bedrooms were added on the west end. A porch was afterwards added to the south side and this became the entrance to the house. A high wall was built along the street on the north side. This was lowered to its present height when the local authorities acquired the building in 1936. The fanciful name “Priory” was given to the house in about 1850.

2. Silver Street This street is probably so named because it leads to Durleigh Brook (Horsepond). There was no medieval Street of this name. No. 6 had a Gothic doorway (now embedded in a shop window). The doorway was probably of Elizabethan date.

3. St. Mary’s Church (The Parish Church of Bridgwater) The 13th century tower is surmounted by a 14th century spire. Guidebooks are on sale in the Church.

4. Glover’s Restaurant (No. 47 St. Mary Street) Basically this is a 16th century building, much altered, which retains the original timber roof. By tradition it is the medieval vicarage.

5. Baptist Chapel This was built in 1837 to replace an earlier place of worship. It has a fine neo-Greek pediment supported by huge Ionic columns.

6. Waterloo House (number 41 St. Mary Street) This is a fine 18th century building built much in the style of Castle Street.

7. Marycourt (No. 39) Tradition insists that this is the house “where Judge Jeffreys slept” although there is no evidence to support the claim. In spite of its medieval appearance the building is of later date. The carving was added in modern times.

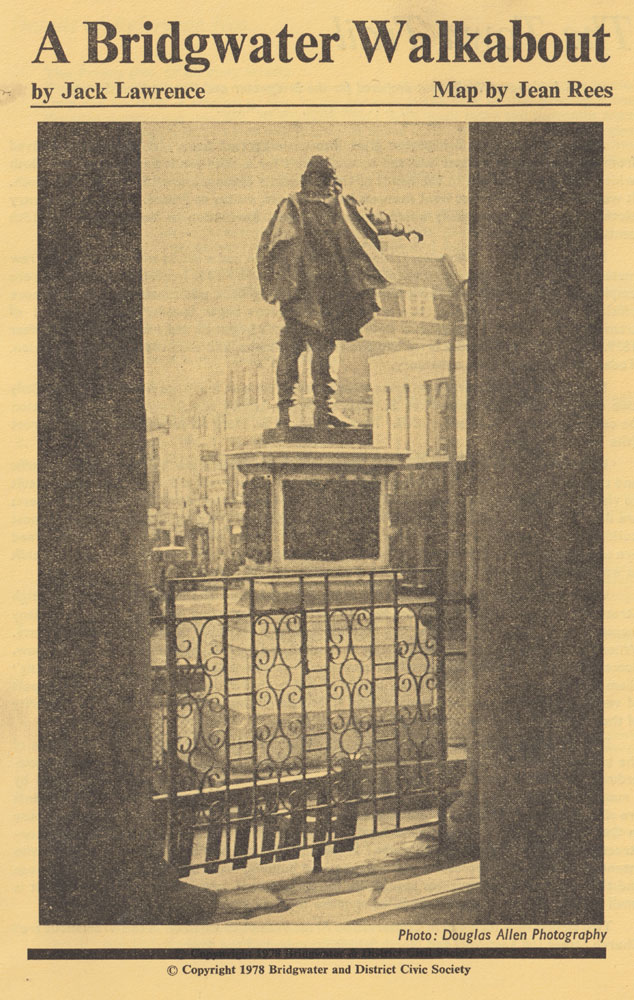

8. The Market House (Cornhill) Our “Cornhill” was the medieval market place. A fine hexagonal 15th century butter cross formerly stood here. There is now a bronze statue of Admiral Blake (by Pomeroy 1900). The Market House was built circa 1839 with a dome and peristyle (On, columns).

9. Royal Clarence Hotel (No. 2 High Street) This was built 1824-5 with well-proportioned windows and a porch with Ionic columns. It is a good example of the Regency style.

10. Westminster Bank (Nos. 9/11 York Buildings) This is a delightful piece of Edwardian baroque (1904).

11. Leeds Building Society (No. 23 Cornhill) This building has an interesting façade of early 19th century date. The architect’s ambitions have not quite come off. This is probably because it is alone of its kind. In Clifton where buildings of similar design stand in groups of three the effect is most satisfying.

12. On the south side Barclay’s Bank (No. 10 Cornhill)

13. Lipton’s (Nos. 8-9 Cornhill) Here we have two four-storied buildings of Italian Renaissance style with a roof parapet, elaborate window mouldings and coign work. They were built about 1845.

14. St. Mary Street There are one or two 18th century buildings on the east side (look for roof parapets and mansards).

15. Crofton Hotel (33-35 St Mary Street) This is late it 19th century building of good design.

16. Tudor Cafe (St. Mary Street) A fake Elizabethan front conceals some genuine 16th century work including very good plaster friezes.

17. Rose and Crown Hotel. Originally this was a medieval house, probably 14th century of which nothing now remains except the bread over.

18. Friarn Street. From the corner, we can see a good shell porch over the door of No. 15. There are other good houses in this street which acquired its name because it went towards the Franciscan Friary which once stood beyond its western end. Avoiding the temptation to walk along it now, we cross the road into Dampier Street.

19. Dampier Street. (Originally Damyate i.e. the Yate or path towards the mill dam). The mill was at the end of Blake Street.

20. The Unitarian Chapel. When this chapel was rebuilt in 1788, the main features of the earlier building (1688) were retained. Above the fine shell porch there is a simple venetian window. The façade is is surmounted by a triangular pediment. Coleridge preached here.

21. Blake Street. Here we find the town museum. Traditionally this is the house where Robert Blake was born. The roof timbers show that the original house was built about 1500 but it has been altered almost beyond recognition. On the opposite side of the street is a good modest 18th century house (No. 6). Before leaving this street we should walk to the end and notice where Durleigh Brook flows into a culvert which still contains some of the machinery of the last mill to work there.

22. Methodist Chapel (corner of King Street) The façade of a building of 1816 was raised in 1860 and a porch was added. The gable reflects the design of that above the Unitarian Chapel.

21. Public Library (Chapel Street) This gives us an Edwardian variation (1906) of the Market house theme.

24. The Turret” Just inside Blake Gardens is a curious little summer house of 18th century date. It was always referred to as “The Turret.”

25. Cottages in Salmon Parade. Looking across the river from Binford Place we see some well designed cottages (early 19th century) one with an iron balcony at the first floor window.

26. Binford Place (Nos. 8 and 9) These are two very dignified examples of late 18th century houses.

27. The Town Bridge (1883) This bridge replaced the first iron bridge which came from Abraham Darby’s works at Coalbrookdale. Before that we had a medieval stone bridge.

28. No. 2 Fore Street. From the corner of Binford Place near the bridge we look across the street at two very different types of building (No. 2 Fore Street and No. I West Quay). No. 2 Fore Street is a brick building which displays a wonderful variety of Edwardian mouldings. The most entertaining feature consists of four terra-cotta snakes which writhe and strike from the four corners of the chimney stack.

29. No.1 West Quay. For many years this building was the Punch Bowl Inn. It has well spaced windows set in a curving wall capped by a roof parapet. It was erected in 1795. The builder, one Joseph Jeffery, had to clear away a jumble of old buildings in order to prepare the site. A grateful corporation granted him a perpetual lease. His only obligation was to pay a ground rent of 5s. 4d. per annum to the local authority. This arrangement will continue until the lease eventually expires in A.D. 3,879.

30. No. 2 West Quay (The Fountain Inn) This building is of similar date to the last one. It has one striking feature — a high gable, almost Dutch in design. This idea is reflected in the hall next door by three semi-circular gables (rather imaginative for 1910). Further along there is another stepped Dutch gable (early 19th century) then a group of 18th century buildings brings us to the corner of Castle Street.

31. East Quay. Looking across the river we see a group of modest 19th century houses, one of which used to be the Post Office.

32. West Quay beyond Castle Street. Continuing our walk along the river we recall that this quay was once crowded with shipping. Further away across the river we can still see the wooden piers of a large wharf very much decayed. Formerly these wharves extended downstream for the best part of a mile. We pass No. 11, an 18th century building recently restored and find the medieval water-gate. This is a simple Norman arch (c. 1200) through which supplies were taken into the Castle. This wall of the Castle stretched from the bridge as far as Chandos Street. At the back of the Water Authority’s car park a portion of the Castle wall is still standing. The Castle occupied an area of some 9 acres, roughly square in shape stretching as far as the west side of King Square. The main gate was at the entrance to the Cornhill in York Buildings.

33. The Lions (1725) This building can claim to be the finest domestic building in the town. Benjamin Holloway, a local builder, erected it for his own dwelling. Many fine features of 18th century architecture are compressed into this imaginative design. Restoration work was carried out in the 1960’s after a serious roof fall, and the two lions which flank the gate were also repaired. Unfortunately the two small pavilions which form an integral part of the design were left in a derelict state.

At this point, if we want to limit the duration of our walk to an hour, we must return to Castle Street, noting the following items, all within reach of this point (Marked.).

34. The Black Bridge. This is a retractable railway bridge constructed in 1871 to bring trucks across the river. It is now to be preserved as a monument of industrial history. Unfortunately the engine which moved the bridge was destroyed in 1970.

35. Beehive Kiln (late 19th century) East of river. Actually there is a group of kilns, one of which is to be preserved as a reminder that before 1939 the town’s prosperity depended largely on the manufacture of bricks and tiles.

36. St. John’s Church (1845, east of the river) This is an early example of the revival of Gothic architecture which accompanied the Oxford Movement.

37. The Docks (straight ahead) The Docks were opened in 1841 and the Bridgwater-Taunton canal was extended from its previous terminal at Somerset Bridge to join the docks. The dockside portion of the large warehouse is contemporary with the dock itself. It was enlarged at a slightly later date when business was brisk. Unfortunately this prosperity evaporated in more recent days and in 1970 the docks were closed. Beyond the docks there is a terrace of cottages (Russell Place).

38. Castle Street This street has been called “the most perfect Georgian Street in Somerset.” Originally it was known as Chandos Street because its design and construction were inspired by James Brydges. Duke of Chandos who became lord of the manor in 1721. The houses on the north side were built and completed between 1721 and 1730. The local builder who carried out most of the work was Benjamin Holloway of “The Lions.” The imaginative designs of four of the doorways were obviously sent down from London by the Duke. The terrace on the south side was never completed. The three houses at its lower end were left as shells in 1730 and were finished at a later date.

Before walking up to King Square we should take a quick look at Queen Street.

39. No. 17 Queen Street. This is not part of Bridgwater Castle, A is a kind of 19th century Folly (see introduction): built to be impressive, it has become hilarious.

40. Court House. A further building with Ionic columns of early 19th century date.

41. King Square. The Duke of Chandos never got round to building on this site. The Constable’s house, still occupied, stood here. Later in the 18th century it fell into ruin and the area became derelict. Eventually the houses on the south side were erected in 180,7 and made a fine terrace. A few years later (1814) the houses on the east side were built. The north side never took shape after the first house had been built in 1830 at the north west corner. 1976 this north side was given “a reproduction façade.‘ which is very much in keeping with the rest of the Square (Bridgwater House).

42. Angel Crescent (To visit this you must walk behind the Clarence Hotel). This group of nine houses sadly neglected (but now listed in the hope of saving them) was built cheaply but with a certain felicity of design, just before 1813. The five houses on the curve all had windows filled in at once to enable them to evade the window tax. You may have seen other blank windows in Nos. 9 and 10 King Square but these were deliberately designed in that way.

43. The High Street. The High Street looks like a typical main street of a market town in which the buildings are a mixture of different styles and periods. The planners must try and preserve its flavour. The most important building is the Town Hall of 1865. The Mansion House Inn is an interesting house with roof parapet and facade of about 1800. But the end wall is of a very much earlier date. This is the probable site of the church house (c. 1500).

The abnormally wide pavement between this point and the Trustee Savings Bank reminds us that for many centuries the High Street stretched right across here., in theory. In practice it had been divided into two narrow streets by an island of buildings. The name of “Bull and Butcher” is a reminder that the medieval butchers’ shops, known as “the Shambles” were concentrated along this frontage.

The keystone above the door of “The Valiant Soldier” bears the date 1583 but the Inn was rebuilt during the 19th century and its appearance completely changed. It stands at the corner of Penel Orlieu. This was originally a market place known as Pig Cross, for it contained a single-shafted cross which was removed in the mid-nineteenth century. The area was re-named Penel Orlieu. The two elements of this name are taken from the names of two medieval streets, Penel or Pynel Street, which ran down Market Street and Orloue Street which was Clare Street. In the 18th century Orloue Street had become “Penel and Orlieu Street.”

We have now come to the end of our tour. In the middle ages the West Gate with a house above it would have stood across the road where we now see traffic lights.

44. If we want to see Friarn Street, we can cross to the south side of Penel Orlieu and turn left alongside Broadway. Here we are already following old Friarn Street, for this section was taken into Broadway, as was Moat Lane on the otherside of the Broadway.

Printed by B.W.W. Printers Ltd..